Remember this astonishing “first image” of the Sagittarius A* (Sgr A) black hole at the heart of the Milky Way? Well, that might not be entirely accurate, according to researchers at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ).

Instead, the accretion disk around Sgr A* could be more elongated than the circular shape we first saw in 2022.

NAOJ scientists applied different analysis methods to Sgr A* data taken for the first time by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) team. The EHT data came from an array of eight ground-based radio telescopes. The original analysis showed a bright ring structure surrounding a dark central region.

The reanalysis resulting in a different shape implies something about the movements and distribution of matter in the disk.

To be fair to both teams, radio interferometry data is notoriously complex to analyze. According to NAOJ astronomer Miyoshi Mikato, the rounded appearance could be due to the way the image was constructed.

“We hypothesize that the ring image resulted from errors during the EHT imaging analysis and that part of it was an artifact, rather than the actual astronomical structure” , Miyoshi suggested.

Explain the appearance of the black hole

So, what does Sgr A* look like in the NAOJ reanalysis?

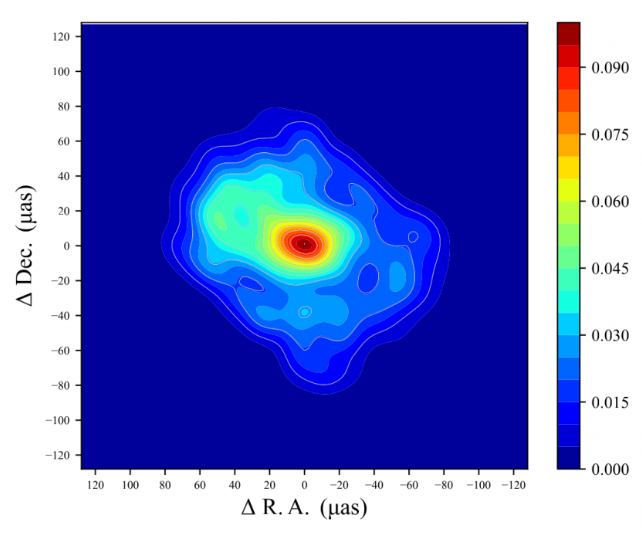

“Our image is slightly elongated in the east-west direction and the eastern half is brighter than the western half,” Miyoshi said.

“We think this appearance means that the accretion disk surrounding the black hole is spinning at about 60 percent of the speed of light.”

The accretion disk is filled with superheated material “circling the drain” so to speak, heading toward the 4 million solar mass black hole. As it passes through the accretion disk, friction and the action of magnetic fields heat the material. This causes it to glow, primarily in x-rays and visible light, as well as emitting radio emissions.

Various factors also influence the shape of the accretion disk, including the rotation of the black hole itself. Additionally, the accretion rate (that is, the amount of material falling into the disk), as well as the angular momentum of the material, all affect the shape.

The black hole’s gravitational pull also distorts our view of the accretion disk. This kind of “funhouse mirror” distortion makes the image incredibly difficult. It turns out that either view of the actual shape of the disk – the original circular EHT view or the elongated NAOJ view – could be accurate.

So why these different views of the black hole?

How did the teams arrive at two slightly different visions of Sgr A* using the same data?

“No telescope can perfectly capture an astronomical image,” Miyoshi emphasized. For EHT observations, it turns out that interferometric data from widely linked telescopes may have gaps. When analyzing data, scientists must use special techniques to construct a complete picture. This is what the EHT team did, resulting in the image of a “round black hole”.

Miyoshi’s team published a paper describing their results. In this paper, they propose that the ring structure in the 2022 image released by EHT is an artifact caused by the irregular point spread function (PSF) of the EHT data.

The PSF describes how an imaging system deals with a point source in the region it is examining. This makes it possible to measure the extent of blur caused by imperfections in the optics (or in this case, gaps in the interferometric data). In other words, he struggled to “fill in” the gaps.

The NAOJ team reanalyzed the data and used a different mapping method to fill gaps in the data. This resulted in an elongated shape for the Sgr A* accretion disk.

Half of the disk is brighter and they suggest this is due to a Doppler increase when the disk is spinning quickly. They suggest that the newly analyzed data and elongated image show a part of the disk located a few Schwarzschild radii from the black hole, spinning extremely quickly and viewed at an angle of 40° to 45°.

What’s next?

This reanalysis should contribute to a better understanding of what the Sgr A* accretion disk actually looks like. The EHT study of Sgr A*, which resulted in the image being released in 2022, was the first detailed attempt to map the region around the black hole.

The EHT consortium is working on improvements to produce better and more detailed interferometric images of this and other black holes. Ultimately, this should lead to more precise views.

Follow-up studies should help fill any gaps in observations of the accretion disk. Additionally, detailed studies of the nearby environment around the black hole are expected to provide more clues about the black hole hidden inside the disk.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.